Wandering Around

Photo: Church Hanborough (Episcopal church), Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom,

The church building is 900 years old, with exceptional features such as a Norman tympanum above the north door, Fr. Dwight Longenecker

Years ago I lived in England and had a job traveling around to different Catholic churches every weekend. This gave me the opportunity to indulge in one of my favourite hobbies—church snooping. Any church is interesting—even modern preaching halls have a homely silence about them. But I admit I don’t usually aim for the Methodist Halls and Baptist chapels. I look out for the old timers. Church snooping in England means pulling up in little villages to explore those humble historic treasures—the ancient parish churches.

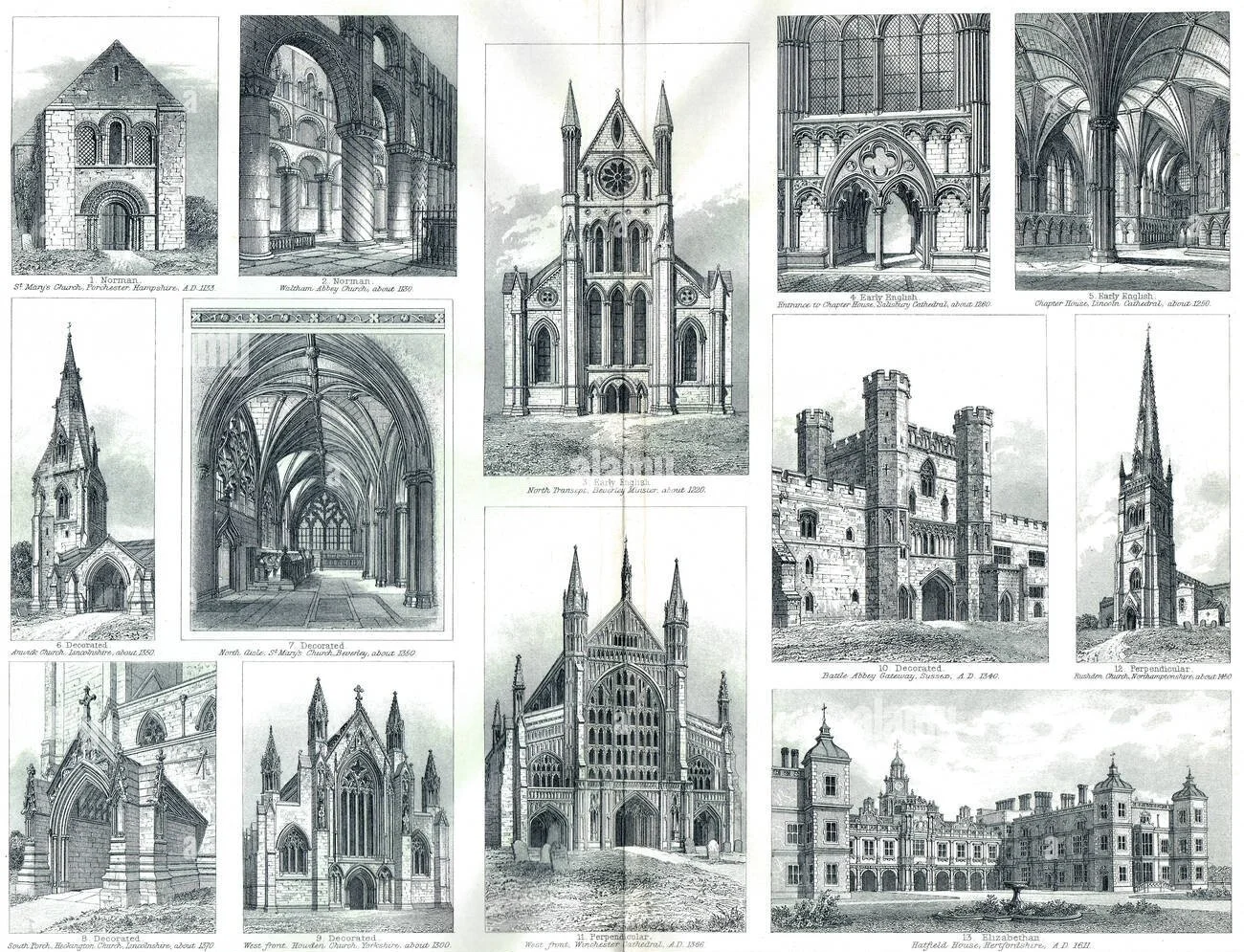

Image: Illustration from the imperial dictionary of the English language published in 1898. Examples of English Gothic architecture from the 12th to 17th centuries, Alamy Stock Photo,

If you know your stuff, you can distinguish the different styles of Norman, Early English, and Perpendicular. You can learn to spot a leper’s window, a Norman font, or a Jacobean pulpit. You learn how to sniff out a blocked piscina, imagine the splendour of the medieval iconography, and tell the difference between a hagioscope and a rood stair.

In the old parish churches a thousand years of ordinary village history is recorded in stone. If you know how to read the record, you can see where the medieval folk processed and stood and prayed. You can see where they buried their dead, and where they lit candles to honour their saints and angels. Sometimes the carvings, glass and paintings have survived and you can see the ghostly images of saints still visible underneath the layers of whitewash. If you know what to look for, you can see the ravaged remains of religious reform and the later furniture of preaching. You can spot the sincere but clumsy restorations of our fervently optimistic Victorian forefathers. Finally there are the signs of the loyal band who maintain the present day church—their devotion to the building perhaps compensating for the religious confusion of their day.

I never get tired of spotting the tower of a distant village, then pulling off the road, traipsing across the ancient churchyard to see if the door might just be open. Philip Larkin recounted the same gentle obsession in his poem Church Going,

Once I am sure there’s nothing going on,

I step inside, letting the door thud shut.

Another church: matting, seats and stone,

And little books; sprawlings of flowers, cut

For Sunday, brownish now; some brass and stuff

Up at the holy end; the small neat organ;

And a tense, musty, unignorable silence,

Brewed God knows how long. Hatless, I take off

My cycle clips in awkward reverence.[i]

I myself, was once the vicar of two of these ‘accoutred frowsty barns.’ I loved sitting in cool dark stillness and leading the people in worship week by week. I loved being physically part of the ancient Church in England. Now I visit the country churches with a sense of sadness, loss and frustration. I feel sadness because I see the Church of England reeling through crisis after crisis. She is a great and glorious church, and it hurts to see her faithful deserting and her leaders locked in strife. I also feel loss because in becoming a Catholic I had to leave my beautiful ancient buildings—my own little share of English ecclesiastical history. But when I visit these old churches I also feel frustration because we haven’t learned the lessons these buildings teach us.

The frustration is real because once I get back in my car I push on to make my visit to a modern Catholic parish. The clash between the country Anglican idyll and the typical modern Catholic parish is huge. The rural Anglican tradition was formed by the likes of George Herbert and Nicholas Ferrar; the Georgian diarist Parson Woodeford and the Victorian country parson and diarist Francis Kilvert. Modern Catholic England—on the other hand—was largely formed by the experience of the poor immigrants in the Victorian cities. Catholic England is strangely cut off from the Anglican experience. This is both an accidental and an assumed position. It seems English Catholics reject all things Anglican on principle.

Anglican culture, with its fine buildings, Oxbridge scholarship, cathedral choirs, bell ringing and fine hymns was rejected not only because so many modern English Catholics were working class, but also because they were from Ireland. Their experience in Ireland of being persecuted by the English naturally led them to reject all forms of English religion. This same tendency seems to have infected English Catholic architecture as well. The first Catholic churches built in England since the reformation were not allowed to look like churches. Even after total Catholic emancipation and the restoration of the hierarchy in the mid-1800s Catholic churches were often intentionally built in a Byzantine, basilica or neo-classical style as a direct statement against the Anglo-Catholic love of the neo-Gothic. Their distinctive Catholic churches were also meant to stand out against the ancient parish churches with their ancient beauty and hodge-podge eclectic style.

With Vatican II the architectural reformers were able to break all links with the past.

In a wave of optimism the new Catholic builders of the late sixties and early seventies developed a style of architecture which can only be called the tee-pee style of church architecture.

The Catholic cathedral in Liverpool is even called Paddy’s Wigwam (pictured above). Built from modern materials of glass, steel and concrete, these Vatican II churches reflected the new attitudes to the liturgy. The reformers believed the Eucharistic liturgy was primarily the gathering of the people of God around the Lord’s table. Hierarchical ideas were anathema and a shallow form of democracy ruled the day. To facilitate the new understanding of the liturgy round churches were built. With an altar at the centre and the people gathered around, the church architects followed Frank Lloyd Wright’s brutal rule of modern architecture—‘Form follows function.’ Suddenly it didn’t matter if a church was beautiful or not. It didn’t matter if it expressed the glory of God. It didn’t matter if it was an effort to reveal the transcendent beauty of worship. What mattered was, ‘Is it liturgically (and politically) correct?’

So on my weekends exploring England I come across these round churches. Often they are plopped down like some huge concrete excrement in a mellow suburb of gracious Victorian houses fronted by rose beds and manicured lawns. Other times they appear in modest inner city housing developments and you have trouble distinguishing between the church and the multi-level parking lot. I have tried very hard to love these churches. Furthermore, I have asked numerous priests and people if they like our own local wigwam of a cathedral. Not one has said they love it. The most positive response I get is from priests who say, ‘It works well liturgically.’ That is fine, but it is not the same thing as loving a building. How can one love a building that is merely functional? Can one love a garage?

Whether the teepee churches actually do fulfil their function is another pressing question. If the function is simply to provide a place for the people of God to gather around the altar, then they fulfil the function admirably. But perhaps part of a church’s function is actually to be beautiful. Isn’t part of its function to lift the mind and heart to God? Shouldn’t a Christian building reflect the great Christian mystery and point beyond itself to the mystery of the incarnation? In other words, perhaps I dislike round churches not because they are functional, but because they are not functional enough.

I have tried to love these modern churches because I dislike the tendency among church people to be whining antiquarians. I don’t believe in a golden age of religion, art or architecture. I believe a man is most often right in what he affirms and wrong in what he denies. I have therefore made a real effort to be open minded. I’ve tried to discover the hidden greatness of our modern tee pee churches. In the end I have failed and turned my energies instead to asking why exactly I dislike such churches. Why do they not lift the spirits? Why do we not find them beautiful? Why do they fail to reflect Christian theology and spirituality?

The answer may be found by looking to the past rather than to twentieth century architectural manuals.

I wonder how many church architects are actually well-versed in the history of ecclesiastical architecture. Do they know church history and the development of Christian architecture? The buildings they design indicate a complete ignorance—perhaps even a willful ignorance of this aspect of the great tradition. If I am right in this suspicion are they not guilty of architectural iconoclasm? They may not pull down the old houses of prayer, but their deliberate ignorance of the tradition indicates a similarly iconoclastic mentality. In fact the tradition of Christian architecture is not totally hierarchical and undemocratic. There has always been plenty of scope to accommodate the communal worship of the people of God. The Christian tradition of architecture was developed from the Old Testament model of the temple, and if we believe the Scriptures were given by inspiration of God, is it too far-fetched to imagine that the Old Testament actually provides a basic model for Christian architecture?

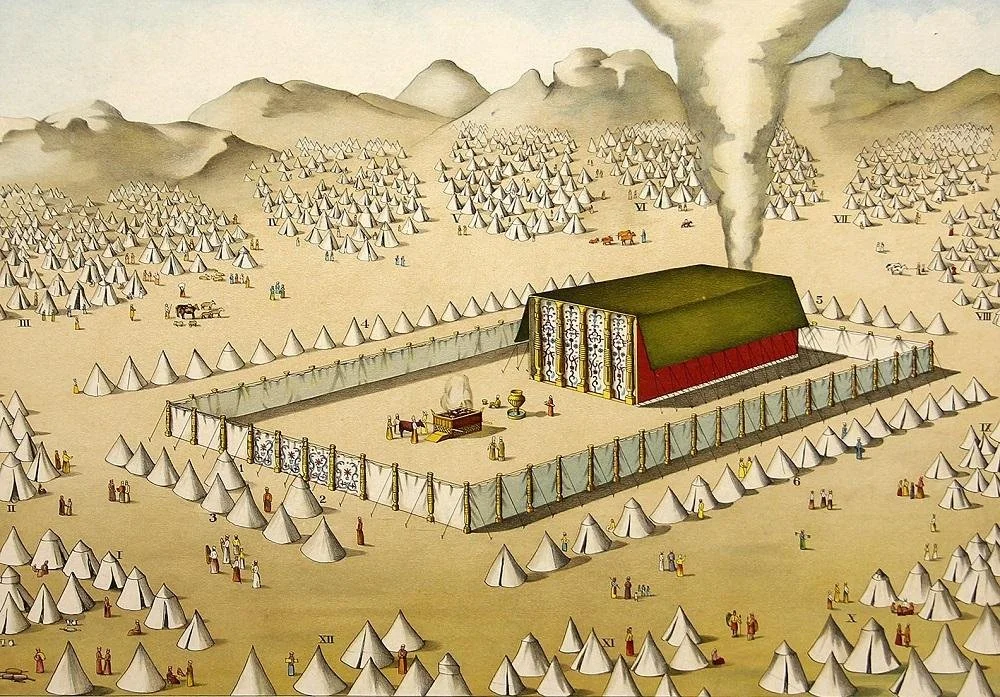

Image: The Tabernacle in the camp, Collectie Nederland

The book of Exodus gives detailed instructions for the construction of the portable tabernacle, and Solomon’s temple was structured on the same basic plan. No one expects Christian churches to be Disney-esque reproductions of Solomon’s temple, but there are some basic principles laid down in the design for the Old Testament tabernacle and temple which should inform Christian architecture. The basic plan of the tabernacle and the temple was that of an outer courtyard for the gathering of the people, then an inner courtyard for the initiates and finally the holy of holies which was separated from the inner court by a great curtain from top to bottom. This pattern gathers together the different functions of a house of worship. The outer court fulfills the function of all the people gathering together for the sacrifice to God. The inner courtyard fulfills the function of a place set apart for prayer and worship. The holy of holies fulfills the function of mystery and transcendence. It gives the sense that the temple is a ‘Bethel’—the house of God. That it is the meeting place of earth and heaven.

This three-fold structure for the temple also re-affirmed the linear aspect of the Judeo-Christian religion. The outer court, inner court and holy of holies provides a focus and direction for the worshipper. There is a front and a back to the church. There is a beginning and an end. The Judeo-Christian tradition is not cyclical. We do not believe in re-incarnation and an endless cycle of birth and re-birth. It is interesting that the Native Americans placed their round teepees in circles around the fire because they believed the whole of nature was cyclical. Christianity, on the other hand, affirms that each individual life and the whole cosmos has a beginning and end—an Alpha and an Omega. A linear structure for our architecture also indicates this sense of forward direction, purpose and ultimate destination.

Up to the nineteen sixties the vast majority of Christian churches followed this basic threefold plan.

Whether the style was Byzantine, Romanesque, Gothic, or Neo-Classical; the three fold pattern was retained. In the Catholic tradition the church could be broken down into nave, chancel and sanctuary. The Catholic tabernacle—traditionally in the sanctuary behind the high altar—was equivalent to the holy of holies. It even has a little curtain inside to reflect the curtain in the temple. In the Orthodox tradition the nave is separated from the sanctuary by the iconostasis or screen. Beyond that is equivalent of the inner court—where the Eucharist is celebrated, and then the ultimate holy of holies or tabernacle. Protestant churches did not follow the pattern so completely, but even they retained a sense of direction and focus with the people turning toward the word of God, the communion table and the baptistry.

In the sixties and seventies we were told to pay more attention to one another. While this attention to our common life was no doubt needed, our whole focus of worship didn’t need to shift from God to ourselves. Catholics are not the only guilty party. I once visited the lively evangelical Anglican church of St Nicholas in Durham. While a certain George Carey was vicar there the Victorian church had been gutted, then carpeted and re-furnished. A preaching platform was constructed on the left-hand wall of the church and portable chairs surrounded the platform in a semi-circle. The church guide was enthusiastic about the worshipper-friendly reconstruction. I commented that the worship was now people centered. She nodded in agreement, but frowned when I added, ‘as opposed to God-centered.’ Worship does not have to be in the round to help build up the common life. It is said that to love our spouses we should love other things with them. Likewise we build a strong Christian fellowship not by looking at one another the whole time, but by gazing in adoration towards our Lord together.

Because we believe in the incarnation of God in our physical world or physical surroundings matter.

Our buildings not only reflect our world view, they help to determine it. The self-help gurus tell us how our clothing influences the way we behave. They would probably also insist that our buildings influence the way we behave. The modern architect’s motto is ‘form follows function’, but what if it were the other way around and function follows form? Could it be that a builder who takes no thought for beauty or transcendence can help to destroy the idea of beauty and transcendence in worship? What if we are influenced as much by the buildings in which we worship as they are influenced by us? Could it be that the dismal state of the liturgy, the lack of reverence and the lackadaisical attitude to the awesome mystery of our religion is as much determined by the buildings in which we gather as it is by our theologians and liturgists?

If one of the functions of a church is to foster devotion and prayer one needs to ask if anyone stops to visit a round church simply to sit still in the silence and to soak in the spirit of the place. Does one look to a round church to contemplate all that lies beyond? Perhaps some do. For me a round church doesn’t help me look anywhere but inward for there is nowhere else to look. A linear church directs my attention beyond myself. The ancient English churches I visit still retain this sense of being a temple of God. In them I want to sit still ‘where prayer has been valid.’ [ii] As Philip Larkin observed, in each church there is the ‘holy end’ which draws the heart and mind toward that ‘musty unignorable silence’—and beyond that to a land and a Lord beyond our imaginings. Even for one who doubts certain certainties reverberate and beckon him to another country.

It pleases me to stand in silence here;

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognised, and robed as destinies.

And that much can never be obsolete,

Since someone will forever be surprising

A hunger in himself to be more serious

And gravitating with it to this ground,

Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in.[iii]

My plea is not to turn back the clock and construct mock medieval churches for the twenty first century. Instead there must be a way to incorporate the beautiful riches of our architectural tradition into the modern world. Do we desire simplicity in our buildings? Nothing is simpler and more dignified than the ancient Roman basilica. Do we desire austerity and restraint? Nothing is more austere and beautiful than the great Cistercian churches. Do we desire an ornate celebration of life? What is more ornate and glorious than full Gothic? Church architects must not slavishly imitate the past, but neither should they be ashamed to study the past and use the great examples of the past for inspiration.

If the tradition can be rejuvenated in this way then there is hope that the churches of the twenty first century will be more than meeting halls. They may once more be temples of the living God, houses of prayer that point beyond themselves and their function to a God whose beauty is far more than his function. Then when we go up to the Lord’s house we may say with the patriarch Jacob, ‘truly this is the house of God, the very threshold of heaven.’