If you are all-powerful, would you desire to be lowly?

(Reflection for the 4th Sunday of Ordinary Time year A)

Sermon on the Mount, by Andrei Mironov

John and Joanne were ministry partners in Church. They met for coffee.

“You need to be careful of Z. I say this with sadness, not judgment”. Said John to Joanne.

“Why?” Asked Joanne.

“Because”, replied John, “Z is two-faced. When Z first joins a ministry, Z will be meek, humble and eager to please.”

“When Z has acquired some status and respectability, the mask comes off. Z will become boastful, start to boss people around, and is not above backstabbing others to get ahead.”

Joanne was troubled. And asked, “Oh, you mean Z only lives the beatitudes because bopian- no choice? (can’t be helped given the circumstances)”

John replied, “That’s one way of putting it.”

Most people, when reading the Sermon on the Mount, as we did in today’s Gospel, would often go away with the notion that this is “high-minded” but probably not practical in real life.

Or as a parent once asked a priest after he had preached this homily, “The world is a cruel place. Should I be teaching my child the beatitudes, or should I teach him survival skills?”

What is more disturbing and ironic about Z was that he actually thinks that the beatitudes are an excellent tool for survival. – if you have no power.

But once you acquire some power and prestige, throw it away quickly. Or at least keep it up as pretence.

Others can be fooled into thinking that you are humble.

But you know what life is really about.

In his book Jesus of Nazareth, Pope Benedict XVI discusses this dynamic when he notes that the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

sees the vision of the Sermon on the Mount as a religion of resentment, as the envy of the cowardly and incompetent, who are unequal to life’s demands and try to avenge themselves by blessing their failure and cursing the strong, the successful and the happy.[1]

For Nietzsche, the beatitudes are not high-minded platitudes.

Instead, he sees in them something more sinister.

That they are, according to him, the teaching of an “evil” genius who teaches the “failures” in life to use it as an ultimate “survival” skill. To wear it as a badge of honour so as to shame the strong.

Once the strong are shamed, and as the failures themselves progress in life, they would, in his words, be “human all too human”[2] and do what Z does.

Use it tactically so that he can acquire more power.

Be prepared to jettison it if it gets in the way of what life is really about.

But what if the Beatitudes are not weakness at all — but God’s form of strength?

In the 4th Sunday of Ordinary time, the readings are arranged in such a way to address this accusation head-on.

The first reading reads like a universal manifesto. One infamous manifesto declared, “workers of the world unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains.”[3]

Zephaniah’s manifesto says instead, “the humble and lowly of the earth unite” for “you will find shelter on the day of anger of the Lord” (Zeph 2:3) and be “able to graze and rest with no one to disturb them.” (Zeph 2:13)

Zephaniah is quick to clarify who the “humble and lowly” really are.

It is not primarily rooted in socioeconomic status. But in the fundamental attitudes and practices of a person.

The humble person, according to Zephaniah, is one who “seek integrity, will tell no lies” (Zeph 2:3) and the “perjured tongue will no longer be found in their mouths.” (Zeph 3:13)

In the first reading, the word “seek” is used three times.

For Zephaniah, qualities like integrity and humility are not simply “bo-pian” attitudes. Just doing it because there is no choice.

Something which is done because someone did a cost-benefit analysis. In Singapore, the law will come down like a hammer on the corrupt, hence better to have integrity as a “survival skill”.

Instead, if you seek something, it is a “be-attitude” i.e., something you actively desire in yourself. Integrity, humility, and having a non-perjured tongue are qualities you actually find attractive. It is its own reward.

And you will seek it for its own sake. For your own happiness.

Or as the responsorial psalm declares

How happy are the poor in spirit: theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Zephaniah’s vision in the 1st reading hints at the connection between seeking integrity and humility and seeking the Lord.

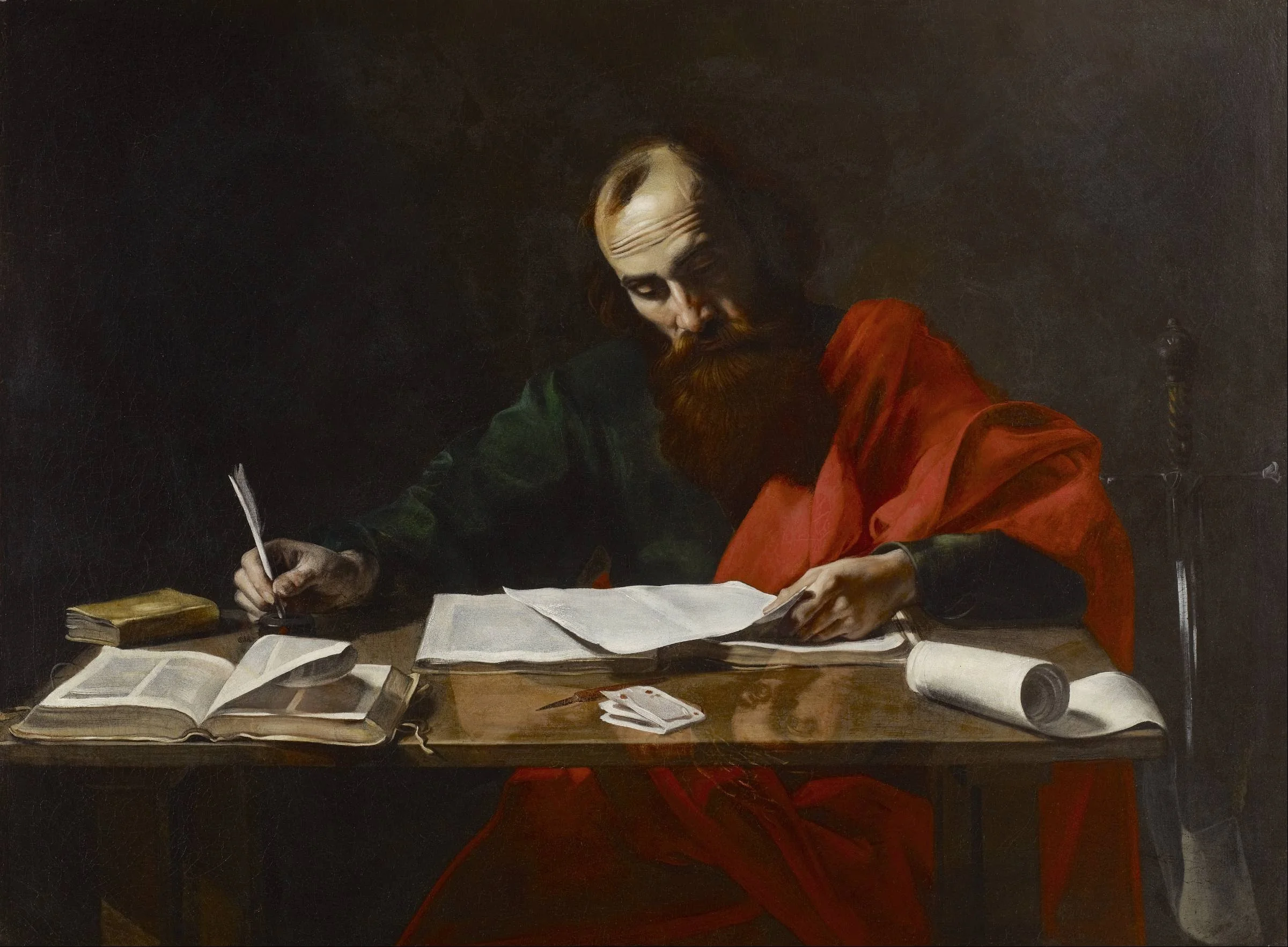

Saint Paul Writing His Epistles (by Valentin de Boulogne)

Paul in the 2nd reading to the Corinthians, recapitulates this theme to a first-century Greco-Roman audience with startlingly similar parallels to 21st-century Singapore.

He takes up a theme which with his training in the Jewish law, he would be thoroughly familiar with.

That the Lord God does not view those in difficult socioeconomic situations as cursed by him.

Rather, he bestows special favour on “those who are bowed down,” (Psalm 146:8) and “protects the stranger and upholds the widow and orphan.” (Psalm 146:9)

Speaking to his Corinthian audience, he points to their social-economic status

how many of you were wise in the ordinary sense of the word, how many were influential people, or came from noble families? (1 Cor 1:26)

The master rhetorician, he knows the answer already.

Not many.

He then goes on to explain why God does this.

It was to shame the wise that God chose what is foolish by human reckoning, and to shame what is strong that he chose what is weak by human reckoning; those whom the world thinks common and contemptible are the ones that God has chosen – those who are nothing at all to show up those who are everything. (1 Cor 1:27-28)

The use of the word shame should give Singapore audiences pause.

Sociologists have often observed that eastern cultures are what they term “face” societies.

A “face” society often places a premium on external appearances and respectability.

And shaming someone, to make them “lose face” in a fundamental and possibly irredeemable sense, so that they can no longer appear in front of others without reproach, is often the worst thing someone can do to another, and can be motivation enough, for people to observe social norms.

Shame is thus a tool to control behaviour.

It is often used by parents as a tool to get their children to perform.

A familiar maxim, increasingly frowned upon, but still stubbornly prevalent, goes like this.

“Ah boy, you see this cleaner? Next time if you don’t study hard, you will end up like him!”

The rubbish collector, in this all too distorted, Singaporean maxim acts as an object to “shame” a child into working harder for his future or risk falling into an irredeemable state of disgrace.

Paul’s preaching turns this maxim on its head.

It is those who are “wise”, “strong”, and who “have everything” by worldly, 1st-century Roman empire standards, who would probably need shaming.

They have Roman citizenship. Have slaves to wait on them. And are part of the leisured class.

And are also the most vulnerable to the deadliest spiritual danger.

Namely, thinking that because of their privileged status, they have actually something to boast about not only to their fellow men, but even to God.

Hence, Paul employs the “nuclear option.”

Shame.

To save them from spiritual ruin.

Paul is emphatic that “the human race has nothing to boast about to God” (1 Cor 1:29)

Whatever one can say about the lowly, they would certainly be more alert to the reality that they have nothing to boast about.

And when you recognise this reality, you would be more open to uniting yourself with Christ Jesus so that he can become “your wisdom, virtue, holiness and freedom.” (1 Cor 1:30)

If Paul were to preach to a 21st-century Singaporean congregation, perhaps he will also turn that infamous maxim on its head.

“Ah boy, you see this cleaner? Jesus also did manual work too you know! Study hard. Find your own way to become like Jesus!”

Becoming Christ is to inhabit his attitudes.

And the sermon on the mount is, as Benedict XVI puts it, a “biography” of Jesus’ inner life and mission. What he says is worth quoting

Anyone who reads Matthew’s text attentively will realise that the Beatitudes present a sort of veiled interior biography of Jesus, a kind of portrait of his figure. He who has no place to lay his head is truly poor; he who can say, Come to me, for I am meek and lowly in heart is truly meek; he is the one who is pure of heart and so unceasingly beholds God. He is the peacemaker, he is the one who suffers for God’s sake.[4]

For Jesus, the beatitudes are never “survival skills.” If he wanted to “survive” in a cruel world, summoning legions of angels would be good enough.

Nor are they simply “duties” he owes to God and carries out faithfully.

They are, in reality, his deepest desires. He who is all-powerful chooses to wash feet, to ride on a donkey, to remain hidden under the appearance of bread.”

And he is teaching the disciples then and even now. Look at my life, in spite of everything, I am a happy man. Do you too want to be happy? Do likewise.

In the words of Benedict XVI

The beatitudes are also a road map for the Church. They are directions for discipleship, directions that concern every individual, even though according to the variety of calling, they do so differently for each person.[5]

[1] Benedict XVI Jesus of Nazahttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workers_of_the_world,_unite!reth (New York: Doubleday 2007) pg 97.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human,_All_Too_Human

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workers_of_the_world,_unite!

[4] Benedict XVI Ibid pg 74.

[5] Ibid 74.